ABSTRACT: Code verification against analytical solutions is a prerequisite to code validation against experimental data. Though solid-mechanics codes have established basic verification standards such as patch tests and convergence tests, few (if any) similar standards exist for testing solid-mechanics constitutive models under nontrivial massive deformations. Increasingly complicated verification tests for solid mechanics are presented, starting with simple patch tests of frame-indifference and traction boundary conditions under affine deformations, followed by two large-deformation problems that might serve as standardized verification tests suitable to quantify accuracy, robustness, and convergence of momentum solvers used in solid-mechanics codes. These problems use an accepted standard of verification testing, the method of manufactured solutions (MMS), which is rarely applied in solid mechanics. Body forces inducing a specified deformation are found analytically by treating the constitutive model abstractly, with a specific model introduced only at the last step in examples. One nonaffine MMS problem subjects the momentum solver and constitutive model to large shears comparable to those in penetration, while ensuring natural boundary conditions to accommodate codes lacking support for applied tractions. Two additional MMS problems, one affine and one nonaffine, include nontrivial traction boundary conditions.

For a copy of the paper along an implementation of the vortex problem, see our simple matlab MPM code.

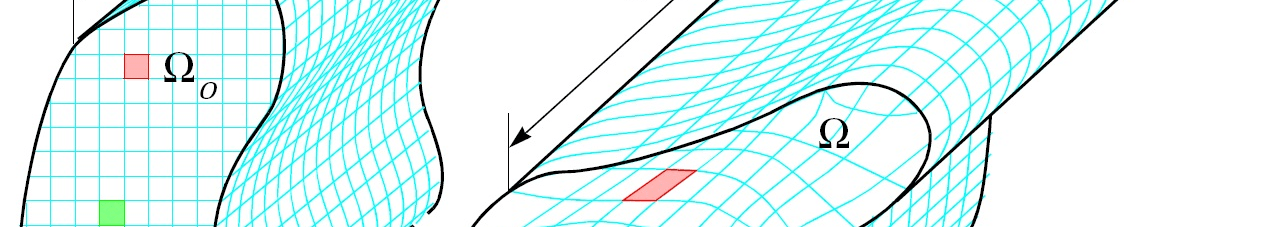

Here are some eye-catching graphics (see the paper itself for details):