H.W. Meyer Jr. and R.M. Brannon

[This post refers to the original on-line version of the publication. The final (paper) version with page numbers and volume is found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2010.09.007. Some further details and clarifications are in the 2012 posting about this article]

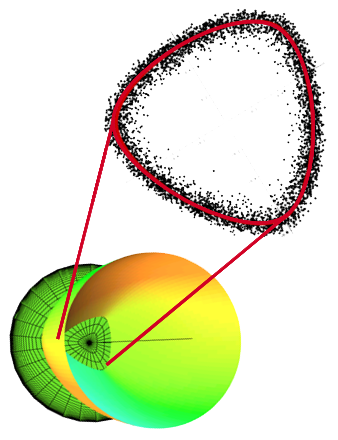

Simulation results for a reference volume of 0.000512 cm^3 ; sf is the size effect factor

Continuum mechanics codes modeling failure of materials historically have considered those materials to be homogeneous, with all elements of a material in the computation having the same failure properties. This is, of course, unrealistic but expedient. But as computer hardware and software has evolved, the time has come to investigate a higher level of complexity in the modeling of failure. The Johnsone-Cook fracture model is widely used in such codes, so it was chosen as the basis for the current work. The CTH finite difference code is widely used to model ballistic impact and penetration, so it also was chosen for the current work. The model proposed here does not consider individual flaws in a material, but rather varies a material’s Johnsone-Cook parameters from element to element to achieve in homogeneity. A Weibull distribution of these parameters is imposed, in such a way as to include a size effect factor in the distribution function. The well-known size effect on the failure of materials must be physically represented in any statistical failure model not only for the representations of bodies in the simulation (e.g., an armor plate), but also for the computational elements, to mitigate element resolution sensitivity of the computations.The statistical failure model was tested in simulations of a Behind Armor Debris (BAD) experiment, and found to do a much better job at predicting the size distribution of fragments than the conventional (homogeneous) failure model. The approach used here to include a size effect in the model proved to be insufficient, and including correlated statistics and/or flaw interactions may improve the model.

Available Online:

http://www.mech.utah.edu/~brannon/pubs/7-2011MeyerBrannon_IE_1915_final_onlinePublishedVersion.pdf

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0734743X10001466